"Braucht gute Architektur Bauvorschriften?"

Ja! 61%

Nein! 39%

{For English please scroll down}

Jaques Herzog hat einmal in einem Interview gesagt, “dass die meisten Architekten gar nicht fähig sind, mit einer Tabula-rasa-Situation etwas anzufangen. Die Einschränkungen und Vorgaben sind für die meisten Architekten das, woran sie sich mangels Fähigkeiten festhalten und woran sie ihr Ding festmachen können“.

Andererseits sind Regeln sind natürlich auch dazu da, gebrochen zu werden. Paul Goldberger meinte dazu in der New York Times sogar einst: „Maybe the best test of a good architect is his or her ability to break the rules and get away with it.“ Es gibt unzählige architektonische Beispiele, die deutlich machen, dass herausragende bauliche Lösungen oft nur dank der hartnäckigen Auseinandersetzung mit Vorschriften und Regeln möglich wurde. Zeitschriften widmen dem Thema ganze Ausgaben, wie z.B. die Bauwelt.

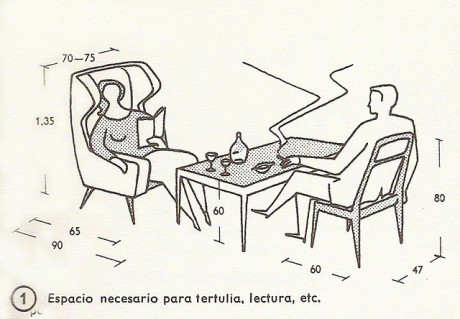

Reibungsfläche sind dabei einerseits Normen und andererseits baurechtliche Vorschriften oder Regeln. Erstere sind insbesondere im Wohnungsbau der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts (und später mit dem Protagonisten Ernst Neuffert) eine Errungenschaft zur Qualitätssicherung des Lebensstandards der breiten Bevölkerung. Sie fliessen ein in baurechtliche Vorschriften, bzw. Bauordnungs- und Bauplanungsrecht, das als politisches Steuerungsinstrument dient, und regelt, ob, was, wie und wieviel gebaut werden darf.

Aber gerade im Wohnungsbau müssen Normen und Regeln immer wieder an die aktuelle gesellschaftliche Situation angepasst werden. Wenn dies nicht geschieht, bleibt Architekten, die sie in kritischer Ausübung ihres Berufes hinterfragen, nichts anderes übrig als sie umzudeuten oder regelrecht auszutricksen. Ohne das Auffinden des gesetzlichen Schlupflochs oder ohne den legalen Regelverstoß durch die Architekten würde heute weder der Tour Bois le Prêtre von Druot, Lacaton & Vassal in Paris noch stehen, noch wäre je die Sargfabrik in Wien (link zum Projekt) entstanden. Standards, die einst zur Qualitätssischerung aufgestellt wurden, können heute zum Beispiel die Erstellung kleinerer und damit günstigerer Wohnungen verhindern. Auch Flächennutzungspläne oder Gestaltungssatzungen fordern Architekten heraus, ihre eigenen Antworten darauf zu finden. Doch wird der Akt der konstruktiven Überschreitung oft genug mit Ausschluss oder Verstümmelung bestraft – man denke an das vermeidbare Schicksal von Nicholas Grimshaws „Gürteltier“, das an der Straßenseite per behördlicher Anordnung auf 22m-Traufhöhe und Blockrandbebauung getrimmt wurde.

Aber darüber zu jammern hilft nicht. Architekten müssen eine aktivere Rolle im Prozess der Normierung und Regelung des Bauens einnehmen. Normen und Bauvorschriften sind bekanntlich nicht gottgegeben, sondern werden von Menschen mit bestimmten Interessen gemacht. Waren das anfänglich eher die politischen Vertreter der Bevölkerung, so haben sich hier in den letzten Jahrzehnten immer mehr die Lobbyvertreter der Bauindustrie ins Spiel gebracht. Immer öfter schreiben sie ihre geschäftlichen Anliegen ganz unverhohlen in die Gesetzesentwürfe, die von den Gesetzgebern nicht selten nur noch durchgewunken werden – man denke an die EnEV, die den Bedürfnissen der Dämmstoffindustrie verbindlichst entgegenkommt. Auf diese Weise ist ein Wust an Vorschriften entstanden, der den einst archaischen Akt des Bauens heute so verkompliziert, dass Architekten immer mehr Zeit damit verbringen, die große bahnbrechende Idee, mit der man den Wettbewerb gewann, auch nur halbwegs unversehrt durch das scharfzackige Heckenwerk unzähliger Paragraphen aus kommunalen, föderalen, Bundes- und europäischen Richtlinien zu bugsieren. Der Architekt wandelt sich langsam vom Entwerfer zum wandelnden Behördenflüsterer. Immer lauter wird der Ruf, die Überregulierung des Bauens zu stoppen. Braucht gute Architektur also Bauvorschriften?

Aktuelle Anmerkung der Redaktion: Angestoßen durch den Britischen Pavillon der letzten Architektur Biennale in Venedig wird das Thema seit einiger Zeit auch in Großbritannien diskutiert (siehe: The Guardian) Und am 5. 3. fand am Royal Institute of British Architects in London ein von Liam Ross organisiertes Symposium zum Thema statt.

Does good architecture need regulations?

Jacques Herzog once said in an interview that: “Most architects are not even capable of dealing with a tabula rasa situation. Restrictions and regulations are what most architects hold on to, for lack of capabilities, in order to anchor their designs somewhere.“

But rules are meant to be broken they say. Former New Yorker architecture critic Paul Goldberger once went as far as saying: “Maybe the best test for a good architect is his or her ability to break the rules and get away with it.“ There are many examples of outstanding architectural designs that only came into being by negotiating, bypassing or even breaking existing regulations. Magazines, like the German Bauwelt, dedicate entire issues to this topic.

Friction is not only caused by general norms but also by regulations or rules. Norms, especially those of housing during the first half of the 20th century, were once used as tools for guaranteeing a good quality of life for the majority of the population. They have been moulded into building code and planning law that today serve as political instruments to regulate what, how, and how much can be built.

But norms and rules have to be adapted continuously to changing social conditions, especially in housing. If this does not happen, then architecture in pursuit of a critical practice will have no other choice but to artfully misinterpret them to reach a perfectly desirable design solution. Without the sophisticated search for legal loopholes, a building like Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris, recently ingeniously transformed by Druot, Lacaton & Vassal, would no longer exist. An equally inventive project, like BKK-3’s Sargfabrik in Vienna, would never have been built in the first place. The same social housing standards first established to guarantee adequate space for dwelling now prevent the production of smaller and more affordable units in cases where that would seem useful (for instance in high-priced real estate markets). On the level of urban design, architects also face the challenge of passing their proposals through a legal corridor of zoning plans and design charters. If architects decide to go against these rules, they are often punished by either having their schemes disqualified from their respective competitions or by being forced to run their designs through a bureaucratic mill that finally spits them out as something entirely different – just remember the pathetic fate of Nicholas Grimshaw’s Chamber of Trade and Industry in Berlin, which on the side facing the street was crudely trimmed to match the standard 22m eaves line of Berlin’s traditional perimeter block.

But there is no point in lamenting over codes and regulations. Architects need to engage more actively in the process of defining the rules. For they are obviously not god-given, but made by people with particular interests. If in the beginning this was the task of our law makers, acting as representatives of society, recently we see lobbyists of the building industry to take an ever more poweful role. It’s not rare that they actually write new regulations which are then only waved through by politicians before becoming actual law. German regulations for saving energy (EnEv), for example, obligingly acts in the interests of the national building insulation industry. In this way, nearly every industrial lobby has managed to slide their particular agenda in some code or other over the past few decades. The result is a tangled mess of regulations that complicates the once archaic act of building, now beyond recognition. Increasingly, architects spend most of their time pushing their project’s one great idea through a vicious labyrinth of paragraphs defined by communes, the state, even the EU. There are increasing calls to stop the endless the proliferation of restrictions. And therefore we ask: Does good architecture need regulations?

Ja ...

Nein ...

Nein ...

Nein ...

Ja ...

Ja ...

Ja ...

Jein ...

Ja ...

Nein ...

Nein ...

Ja ...

Ja ...

Jein ...

Ja ...

Nein ...

No, we’re not convinced that good architecture needs building regulations. Regulations are surely necessary to help organize society, but they don’t necessarily create good architecture. We have seen a lot of good architecture in our lives that was produced in situations with few or no building regulations. For instance, we spent a lot of time in Niger in Africa after graduating from architecture school. In this developing country the organization of daily life is not a routine but an existential act. Building a house is a very immediate translation of basic needs into a space – such as wanting to have some shadow or a cool breeze. Together with a very careful attention to the environment, orientation and climate, that’s what generates the architecture of that place. Norms and regulations are replaced by observation, common sense and knowledge.“

There is a beautiful novel by José Luis Borges called „The Exactitude of Science“. It’s about a guild of cartographers and their attempt to produce a 1:1 map of the Empire. When the cartographers finished the map, it completely covered the world it was pretending to represent. Regulations are similar to this map. Trying to cover everything, they easily miss many precious and relevant aspects of reality. Rather than regulations we prefer to take the real world as our reference when adding something to it. For the Café at the Architecture Center in Vienna, we designed the ground plan so that you have to pass through the kitchen on your way to the toilets from the dining hall. Because this was not in accordance with the sanitary laws of Vienna, the city’s building department first denied our building permit. Luckily, we discovered the same spatial sequence in Café Prückel, one of Vienna’s most prestigious Kaffeehäuser, where you pass by an open kitchen on your way down to the bathrooms. Since Prückel is a highly classic cultural institution in Vienna, no one would dare to question it. The regulators of the city therefore agreed to take the Prückel as a precedent and let us get away with the same programmatic sequence for our project.

Regulations can also stifle innovation. The new energy-saving regulations for buildings in Europe for instance are based on a very reductivist thinking: to prove that a building is sufficently insulated, you have to calculate the U-Value of the materials on its facade. But this formula does not work for every building—not for our transformation of Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris, for instance. There we replaced the building’s asbestos-contaminated facade with a double facade that consists of a two meter deep winter garden and a one meter deep balcony. Now the building is thermally insulated thanks to the double-glazed sliding doors of the inner-most facade, a thermal curtain, and, most impotantly, by the passive solar heat gain of the winter garden. This layered facade acts as a thermal buffer that decreases the temperature difference between the outdoor and indoor climate. We can thus reduce the building’s heating energy by 60 %! But not by wrapping the construction with styroform, as conventional regulations would have wanted us to, but basically enveloping it with a a volume of air. And unlike a styroform wall, that volume contains usable space.

It is but one example which clearly shows, in my opinion, that architects must not accept building regulations as god-given and absolute. Since our built environments continuously evolve, the rules invented to regulate them also need to be checked constantly to see if they still apply—and if they don’t, they need to be changed.

Anne Lacaton directs, together with her partner Jean-Philippe Vassal, the French architecture office Lacaton & Vassal architectes. Through a series of internationally recognized housing projects Lacaton & Vassal have redefined the social dimension in social housing as well as reinstating the cultural legacy of modernist pre-fab mass housing developments in France and beyond. Their „Tour Bois Le Prêtre“, a signature case-study project of this research, is currently presented in an exhibition at the DAZ, Berlin.

5

0

4

Nathalie Janson / 11.3.2013 / 13:55

Jein ...

This approach is radical and also very convincing—but how do you prove to the regulators that this form of "air insulaton“ is efficient, when they most likely expect the usual styrofoam wrapper?

Anne Lacaton / 11.3.2013 / 16:45

Nein ...

Ilka Ruby / 14.3.2013 / 1:02

Jein ...

Anne Lacaton / 14.3.2013 / 17:05

Nein ...